Tibet (Classical Tibetan: Bod; , Lhasa dialect: Pö; Mandarin Chinese: 西藏, Xīzàng) is sometimes described as the "roof of the world"; the entire region is on a high plateau and there are many large mountains. The area has its own unique culture, and most travellers will find some of the plants, wildlife and domestic animals quite exotic as well. Entering Tibet you feel as though you've found an entirely different world.

Politically, Tibet is an autonomous region of China, but there is an independence movement and even a government-in-exile headed by the former ruler, the Dalai Lama. For discussion, see the Understand section below. Travellers who disagree with the current political situation may think they have an ethical dilemma because if they go to Tibet they feel they are implicitly supporting the Chinese regime, with some of their money going to the Chinese authorities. However the Dalai Lama encourages foreigners to go, so that they can see the situation for themselves and because Tibetans welcome their presence.

Politically, Tibet is an autonomous region of China, but there is an independence movement and even a government-in-exile headed by the former ruler, the Dalai Lama. For discussion, see the Understand section below. Travellers who disagree with the current political situation may think they have an ethical dilemma because if they go to Tibet they feel they are implicitly supporting the Chinese regime, with some of their money going to the Chinese authorities. However the Dalai Lama encourages foreigners to go, so that they can see the situation for themselves and because Tibetans welcome their presence.

Tibet is also becoming a more and more popular travel destination among the Chinese themselves. It is almost as exotic to someone from another area of China as it is to someone from the other side of the world, and there is now a good rail link.

There are seven prefectures in the Tibet Autonomous Region:

This article only covers the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), although there was once a Tibetan Kingdom considerably larger than the autonomous region's current borders.

To learn more about other regions that are culturally affiliated with Tibet, see the Chinese provinces of Qinghai and Yunnan; the Indian regions of Ladakh, Lahaul and Spiti, and Sikkim; and the independent states of Bhutan and Nepal.

- Lhasa. - the capital of Tibet

- Gyantse.

- Qamdo. (Chamdo)

- Xigatse. (Shigatse) - the second largest city in Tibet

Lhasa. - the capital of Tibet

Gyantse.

Qamdo. (Chamdo)

Xigatse. (Shigatse) - the second largest city in Tibet

- Mount Kailash. - a sacred mountain revered by both Tibetan Buddhists and Hindus.

- Qomolangma National Nature Reserve. - the Tibetan side of Mount Everest

- Yarlong River National Park. containing the world's largest canyon, the Yalung Zangbo Canyon.

Mount Kailash. - a sacred mountain revered by both Tibetan Buddhists and Hindus.

Qomolangma National Nature Reserve. - the Tibetan side of [[Mount Everest]]

Yarlong River National Park. containing the world's largest canyon, the Yalung Zangbo Canyon.

This article covers only the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR). There are also Tibetan autonomous prefectures and or counties located in the provinces of Qinghai, southwest Gansu, western Sichuan and northwest Yunnan, covered in the articles on those provinces. See List of Chinese provinces and regions for an explanation of the terms "autonomous region" and "autonomous prefecture" if required.

The Tibetan Empire was once much larger than the current borders, and various areas outside the TAR are culturally, historically and linguistically Tibetan to various degrees. In contemporary China, and in general English usage today, the term "Tibet" refers only to the TAR. However, the term "Tibetan Regions", with its focus on all of ethnographic Tibet is becoming more widespread amongst Chinese in China as well.

The Tibetan Plateau is the world's largest and, with average heights of over 4,000m, also the world's highest, plateau. It includes all of the TAR, most of Qinghai, and parts of Sichuan, Yunnan and Gansu. Parts of the region (northwestern region) are so remote they remain uninhabited to this day.

India and the rest of Asia are on separate continental plates which are colliding; that collision is what raised the plateau to its current height. Most of the world's highest mountains are in the Himalaya range along Tibet's southern border, along the line of the subduction zone where one plate goes under the other. Mount Everest, the highest of all, is on the border between Tibet and Nepal.

Tibet has a long and complicated history, at times an Empire, at times warring with China, and at times a tributary of China or the Mongol Empire. It first came under common rule with China when the Mongols conquered both around 1300.

For most of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), Tibet was nominally part of the Chinese Empire and there was a Qing official called an Anban in Lhasa who had tremendous influence, but the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama (high-ranking religious figures) actually ran things.

Britain sent a force to Lhasa in 1904/05, but the Anglo-Russian agreement of 1907, widely seen as the end to the Great Game (a competition for influence in Asia between those empires that lasted most of the 19th century), stipulated that neither country would interfere in Tibet, leaving it in China's sphere of influence. In 1910, Qing China sent a military expedition of its own to Tibet for direct rule.

However, after the Qing Dynasty fell in 1911, Tibet declared independence under the authority of the 13th Dalai Lama. Tibet was an isolated de facto independent nation for almost forty years; its borders were larger than the current TAR and included what are now portions of Qinghai, Sichuan and Yunnan. The Chinese government, however, never accepted their claim to independence.

After the retreat of the Nationalists to Taiwan and the founding of the People's Republic in 1949, the Communists turned their attention towards Tibet as they wished to consolidate control over all former Qing territories. In 1950, the People's Liberation Army (PLA) invaded Tibet. In the UN Security Council, the Nationalists (who still had China's seat) vetoed a motion that would have censured the invasion; they too considered Tibet part of China.

In 1951 an agreement was signed that annexed Tibet into China, giving Tibet — on paper — full autonomous status for governance, religion and local affairs. The current (14th) Dalai Lama was even made a vice-secretary of the Chinese Communist Party in the early 1950s. However communist reforms and the heavy-handed approach of the PLA led to tensions. After a failed Tibetan Uprising in March 1959, the Dalai Lama and many of his followers went into exile in India, setting up a government in exile in Dharamsala. Each side accuses the other of failure to live up to the 1951 agreement. The CIA assisted the uprising and Chinese propagandists still mention this often.

Tibet's isolated location did not protect it from the terror of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), and large numbers of Tibetans were killed or imprisoned at the hands of the Red Guards. Tibet's rich cultural heritage as well as much of neighboring Chinese ancient culture were reduced to ruins. After the end of that era, the rise of Deng Xiaoping and China's "reform and opening up" policies since 1978, the situation in Tibet has calmed considerably, though it still remains tense. Monasteries are slowly being rebuilt and a semblance of normality has returned to the region. Despite this, Tibet still suffers from independence-related civil unrest from time to time. The Chinese authorities often close Tibet to foreign tourists, usually in March, the anniversary of the 1959 uprising.

When the 10th Panchen Lama died in 1989, other lamas selected a new one, as was customary in Tibetan tradition. The Chinese government, however, did not accept this and instead installed a different boy as their officially-recognised Panchen Lama. The lamas' appointee disappeared shortly after, and has never been heard from since.

To a considerable extent, the issues in Tibet are the same as for indigenous peoples anywhere, such as Uyghurs in China's western province Xinjiang or the native peoples in North or South America. The government points proudly to development work such as mines, railways and highways; locals complain that those facilities are all owned by outsiders, outsiders get most of the good jobs while locals do most of the heavy work, and environmental consequences are often ignored. The government say they are improving education; locals complain that the system aims at forcing assimilation by using a language foreign to them. Immigration is encouraged and sometimes subsidized; locals complain of an influx of outsiders that do not want to adapt to local culture and often do not even bother to learn the local language. When the locals get really agitated, the government does not hesitate to send in troops to "restore order"; generally the locals see this as vicious repression, but the government claim they are only dealing appropriately with "hostile Indians", "reactionary elements" or whatever.

The question of Tibetan sovereignty is a hot-button issue in China. The Party Line is that Tibet has always been part of China and foreigners have no business meddling in internal Chinese affairs. There was no invasion in 1950, only the central government asserting its authority over a province to liberate it from a severely oppressive feudal system, a corrupt medieval theocracy with slavery. (That part makes a lot of sense to Chinese, liberated from their own feudal system in 1911.) Western powers are being extremely hypocritical since they roundly condemn theocracy (rule by priests) in Iran and simultaneously support it in Tibet. Many Chinese people agree with the government position, and some of those will ask foreigners about Tibet then firmly "correct" their "errors". Avoiding such discussions is a good policy.

As of 2018, the Chinese government has begun to clamp down on Buddhist religious observances in Tibet, and children under the age of 16 are barred from entering temples or participating in any form of religious activity.

- Eight Years in Tibet by Peter Aufschnaiter and Martin Brauen

- Dialogues Tibetan, Dialogues Han by Hannü: Tibet through the Tibetans with a Han traveller

- Tears Of Blood: A Cry for Tibet by Mary Craig

See also: Tibetan phrasebook

The main language of Tibet is Tibetan; which comes in many varying dialects, but many Tibetans speak or understand some Mandarin except the nomadic tribes in the Far East Tibet. Tibetan is closely related to Burmese and much more distantly to Chinese. Depending on the dialect of Tibetan spoken, it may be tonal or non-tonal. In the cities people speak Chinese fluently; in the villages it may not be understood at all. Han Chinese people, on the other hand, normally don't know any Tibetan at all. Signs in Tibet, including street signs, are at least bilingual - in Chinese and in Tibetan - plus a major local language when there is one.

Although this makes Chinese a more useful language for travellers in many ways, you should remember that language can be political in this charged environment. If you speak in Chinese to Tibetans you are associating yourself with the Chinese, the presence of whom is often resented among the ethnic Tibetan population, as evidenced by the widespread rioting throughout the region in the run-up to the Olympic Games. That said, many Tibetans seem to view Chinese as a useful lingua franca and a few Tibetan pleasantries are enough to befriend Tibetans. Tibetans from different regions converse in Chinese since Tibetan dialects vary so much that they are not immediately mutually understandable. If you speak Tibetan to Chinese police you'll raise suspicions that you may be in Tibet to support Tibetan Independence.

Tibetan is, however, an extremely difficult language to learn, and most foreigners who claim to know Tibetan can hardly get by. Tibetan is only taught in school until the 8th grade. Therefore, when it comes to writing, even the Tibetans themselves have difficulties and many are in fact illiterate.

- The Potala Palace, the home of successive Dalai Lamas is in Lhasa

- The Jokhang Temple in Lhasa was built in 647 AD by Songtsen Gampo and is one of the holiest sites in Tibet.

- The Barkhor in Lhasa is the name for the ring of streets of traditional Tibetan buildings surrounding the Jokhang Temple.

- The 'Norbulingka (Summer Palace of the Dalai Lama) is located in Lhasa, about 1km south of the Potala.

- Samye Monastery - constructed in 779 AD, Samye was the first Buddhist Monastery established in Tibet, and is located near Dranang, Shannan Prefecture, 150 km south-east of Lhasa.

- Tashilhunpo Monastery, the traditional seat of the Panchen Lamas. It was constructed in 1447 and is located in Shigatse.

- The Rongbuk Monastery, one of the highest monasteries in the world, from which the view of the Mt. Everest is just amazing.

The Potala Palace, the home of successive Dalai Lamas is in [[Lhasa]]

The Jokhang Temple in [[Lhasa]] was built in 647 AD by Songtsen Gampo and is one of the holiest sites in Tibet.

The Barkhor in [[Lhasa]] is the name for the ring of streets of traditional Tibetan buildings surrounding the Jokhang Temple.

The 'Norbulingka (Summer Palace of the Dalai Lama) is located in [[Lhasa]], about 1km south of the Potala.

[[Samye#See|Samye Monastery]] - constructed in 779 AD, Samye was the first Buddhist Monastery established in Tibet, and is located near Dranang, [[Shannan (prefecture) |Shannan Prefecture]], 150 km south-east of Lhasa.

Tashilhunpo Monastery, the traditional seat of the Panchen Lamas. It was constructed in 1447 and is located in [[Shigatse]].

The Rongbuk Monastery, one of the highest monasteries in the world, from which the view of the Mt. Everest is just amazing.

Trekking is a major draw in Tibet, with Mount Kailash (Lake Manasarovar) and Everest Base Camp (5200m) in Qomolangma being the best-known attractions. Both are remote and challenging, generally requiring at least ten days in Tibet to complete.

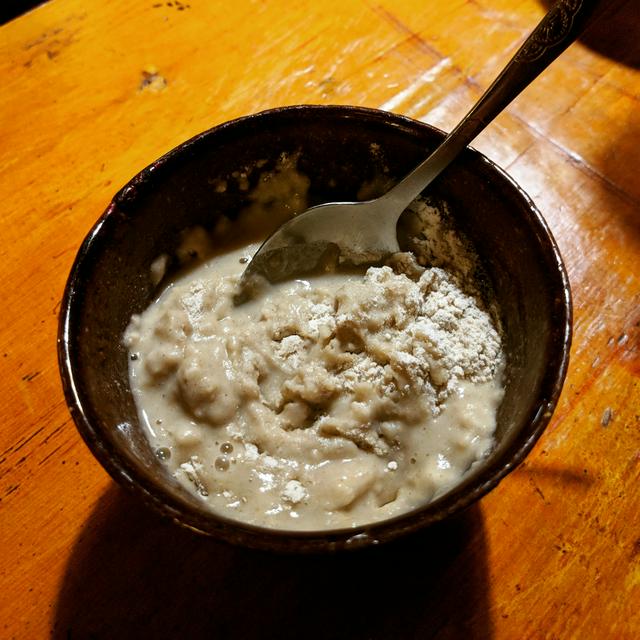

Tibet is not a country people visit for the cuisine. The traditional Tibetan diet is largely limited to barley, meat (mutton or yak) and dairy products, with very few spices or vegetables, although brutally hot chili sauce may be served on the side. Even good Tibetan food is very monotonous with most Tibetan restaurants serving nothing other than thukpa (noodle soup) and tea. A selection of popular Tibetan fare:

- Momos - dumplings filled with meat or vegetables, steamed or fried

- Tingmo - bland, nearly tasteless steamed bread

- Thukpa - a hearty noodle soup with veggies or meat

- Thenthuk - thukpa with handmade noodles

- Yak butter tea - salty tea churned with butter, a Tibetan staple and a rather acquired taste for most Westerners (see Drink)

- Tsampa - roasted barley flour, a common travel food and temple offering, usually eaten by mixing it with butter tea to create dumplings or porridge

Restaurants in Tibet can broadly be categorized into three groups:

- Tourist restaurants catering to non-Chinese, which have near-identical English menus of foreigner-friendly Tibetan fare, some Nepalese dishes, and varying successful attempts at Western food like pizza, spaghetti and hamburgers. While comparatively few, you will likely eat most of your meals in these, because your tour guides will inevitably take you to these places: not only is the food "safe", but they pay the best commissions too.

- Chinese restaurants catering to ethnic Chinese, serving authentic but often delicious Chinese food (fearsomely spicy Sichuanese is prominent) and Chinese-friendly Tibetan fare like yak hotpots. Some travellers feel that Hui (ethnic Chinese Moslem) places are cleaner because of halal food laws; they can be recognised by the green flags and crescent moons (and because they do look cleaner).

- Tibetan restaurants/tea shops catering to Tibetans, serving drinks and a very limited range of Tibetan food, often just thukpa noodle soup.

Despite being a predominantly Buddhist country, Tibet is not particularly vegetarian-friendly - the altitude being the main justification for this. In rural areas, vegetarians need to be prepared to compromise or live on very simple diets. Even if a thukpa is without meat, you can bet the broth they use is a meat broth.

However, monastery restaurants and some large towns do offer restaurants serving vegetarian food and even some Tibetans observe a vegetarian diet on particular days of the religious month. So it is worth asking. One key term to look out for is དཀར་ཟས་ (literally, "white food" - kar zey) which you will see, for example, on some monastery restaurants or in Lhasa, where there are Tibetan vegetarian restaurants. In spoken Tibetan, vegetarian food is also simply referred to as "without-meat-food" ཤ་མེད་ཁ་ལག sha mey kha la.

Yak butter tea - salty tea churned with butter, a Tibetan staple and a rather acquired taste for most Westerners (see [[#Drink|Drink]])

Tea houses are an important social venue in Tibet, and offer a chance to sit down and relax. The tea houses in the larger towns and cities offer sweet milk tea, salted black tea or salted butter tea; in the villages you may only have the option of salt tea. The line between a tea house (ཇ་ཁང་ cha khang) and a restaurant (ཟ་ཁང་ za khang) is blurred and many tea houses also offer thukpa noodle soup.

Tibetan butter tea (བོད་ཇ pö cha, Chinese 酥油茶 sūyóuchá) is a must try, though it may not be a pleasant experience for all — even the Dalai Lama famously said that he's not a fan of the stuff! It is a salty mixture of black tea and Tibetan butter. Traditionally it is churned by hand with a thick rod in a long upright wooden container. However, when electricity came to the city in recent years, modernized Tibetans turn to use electric mixers to make their butter tea. The Tibetan butter is not rancid as commonly described, but has a cheesy taste and smell to it, close to blue cheese or Roquefort. Think of it as a cheese broth rather, that you will appreciate particularly after a long hike in cold weather.

An alternative to Tibetan butter tea is sweet milk tea (cha ngar mo) which is more familiar to western palates. Sweet tea drinking was introduced only recently by merchants returning from India, first among well-off Tibetans, since sugar was a luxury on the Plateau, then when sugar became more available among the general public. Unlike Indians, Tibetan do not use spices (clove, cinnamon, cardamon) to flavor their tea.

Salted black tea (cha thang) is another alternative, refreshingly free from milk or butter!

When ordering tea in a teahouse, the price is usually for a full thermos bottle of the stuff, not a single cup.

Chang, or Tibetan beer made of barley, has a lighter flavour than a Western-type, bottled beer, since they do not use bitter hops. Often home-brewed and with as many taste and strength variants as industrial beers, but the blue cans of Shigatse Chang sold in restaurants and shops around Lhasa are quite mild-flavored and low in alcohol (around 1.5%).

While a comparatively recent import, Western-style beer is also widely available, particularly the rather light/bland locally brewed Lhasa Beer. Various Chinese-style baijiu spirits are also sold, often with herbs of dubious medicinal value blended in.

Plan your route to manage altitude sickness; the main thing is to give your body enough time to acclimatize before going higher. This is important both when getting in, and when ascending within Tibet. Be prepared to adjust your plans, descend or spend a few extra days acclimatizing if it proves necessary.

You are very high up, the sun is going to be very strong; see sunburn and sun protection. Wear protective clothing, UV-protective sunglasses, and sunscreen.

When travelling in the countryside be prepared for the vehicle to break down and for bad weather. Carry a snack and some warm clothes. Water and fluids are essential.

Be warned that driving at night can be particularly dangerous in Tibet.

Beware of the dogs! In the cities there are numerous stray dogs about and in the country side the villagers and nomads keep large guard dogs for security, (usually chained up). A modest level of caution is enough to prevent you from being bitten, as the strays usually run in packs and if you don't get too close you should be okay. If guard dogs are unchained, keep them at bay by staying away from the house or tent they are protecting at all costs as their barking will indicate they have picked you up on their radar and pray they don't come running after you. If they do, pick up (or pretend to pick up) some stones and be prepared to be attacked at the ankle. Sometimes kicking or lunging at the dogs before they attack may scare them off. Some other ways to protect yourself is by wearing boots and thick pants. Much is made of the viciousness of the Tibetan dogs, but few travelers have problems with them. See also aggressive dogs.

Steer clear of political protests. They're rare, but suppressed brutally by the authorities, who do not look kindly on Western witnesses (especially those with cameras).

- Avoid placing any Tibetan at risk by discussing political matters. This includes anything about the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan Government-in-Exile. While you're unlikely to get in trouble, a casual comment overheard by the wrong person may risk them their job or land them a spell in prison.

- Be respectful and cooperative when your papers are checked or bags inspected, which they will be, often multiple times per day. That said, foreigners are rarely if ever hassled and your tour guide will take care of the vast majority of the paperwork anyway.

- Travellers to Tibet usually find Tibetans to be friendly. It is appreciated when you try and use the local Tibetan dialect when communicating with Tibetans. The further from Lhasa you travel, the more often Tibetan is used.

- Religion is extremely important to the majority of Tibetans, and travellers should endeavour to respect their customs and beliefs. Always walk around Tibetan Buddhist religious sites or monastery in a clockwise direction, and when in a monastery do not wear a hat, smoke or touch frescoes. In addition, refrain from climbing onto statues, mani stones or other sacred objects.

- Do not take photographs of police, military, checkpoints, etc. Don't photograph people without permission; photography inside temples and palaces is generally prohibited unless you pay fees ranging from reasonable to extortionate. Sky burial sites are obviously off-limits.

- Tibetan Buddhism and its impact on Tibetan culture is a major draw for tourists. Funds used to pay entry fees at major religious sites will probably go into the coffers of the local Communist Party and its Chinese members. Funds donated directly to individual monks and nuns and left on altars will remain and be used to maintain and support the local religious infrastructure. Appreciate the work of the monasteries and those within and help support these great institutions with non-monetary donations and by attending the festivals and just spending a little time getting to know the monastic community.

- Supporting the Tibetan economy by purchasing from Tibetans is a great way to help. Pay a fair price while bargaining. Beware that some vendors may try to swindle tourists by selling at very high prices.

- Help protect Tibet for future generations by not purchasing products made from wild animals. Many items are made from endangered species. Remember to leave only footprints and take lots of photographs while visiting Tibet. Take the initiative and pack out trash and recyclables you see around while travelling outside of urban Tibet. The ecosystem in the Himalayas is very fragile due to the weather being so cold, so be careful of where you hike and try to keep erosion down.

- Help to keep Tibetan culture alive. It is very important to use Tibetan resources such as hotels, restaurants, guides and souvenir stalls, as Tibetan culture is gradually being eroded. It is also important to benefit financially the Tibetans, who are rapidly becoming a disadvantaged minority in their own country. When visiting temples, monasteries or shrines you may wish to leave a donation, which will help their upkeep. It is best to leave it on the altar or give it directly to a monk or nun. This will ensure it stays in the temple. You may also wish to give a small donation to pilgrims from rural Tibet.

Generally speaking, it is easier getting out of Tibet than in, however, to the south the Himalaya rises even higher, presenting a formidable barrier to travel.